Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (August 29, 1780 – January 14, 1867) was a French painter. His name is pronounced in French (i.e. final -es is not pronounced).

Life

He was born in Montauban, Tarn-et-Garonne, France. His father was a painter, sculptor and violinist, and taught the young Ingres in all these disciplines. The boy's talent for music seemed most promising at first — performance of a concerto of Giovanni Battista Viotti was applauded at the theatre of Toulouse. In 1791 he entered the Royal Academy of Arts in Toulouse where he studied art under Joseph Roques, sculpture under J. Vigan, and landscape painting under Briant.

In 1796 Ingres went to Paris to study under Jacques-Louis David, where he studied for four years, finally wining the Grand Prix in 1801 for Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the tent of Achilles. He parted company from David over a difference of opinion on style. Ingres's style was more flat and linear, and focused on contour.

Napoleon on his Imperial throne, 1806In 1802 he exhibited Girl after bathing and in 1804 a Portrait of the First Consul. These were followed in 1806 by Napoleon on his Imperial throne and a series of portraits of the Rivière family. These works produced a disturbing impression on the public. It was clear that the artist was some one who must be counted with; his talent, the purity of his line, and his power of literal rendering were generally acknowledged; but he was reproached with a desire to be singular and extraordinary. "Ingres," wrote Frau v. Hastfer (Leben and Kunst in Paris, 1806) "wird nach Italien gehen, and dort wird er vielleicht vergessen dass er zu etwas Grossem geboren ist, and wird eben darum ein hohes Ziel erreichen." In this spirit, also, Chaussard violently attacked his portrait of the Emperor (Pausanias Francais, 1806), nor did the portraits of the Rivière family escape. The points on which Chaussard justly lays stress are the strange discordances of colour such as the blue of the cushion against which Madame Rivière leans, and the want of the relief and warmth of life, but he omits to touch on that grasp of his subject as a whole, shown in the portraits of both husband and wife, which already evidences the strength and sincerity of the passionless point of view which marks all Ingres's best productions.

Madame Rivière, 1806The very year after his arrival in Rome (1808) Ingres produced Oedipus and the Sphinx, a work which proved him in the full possession of his mature powers, and began the Venus Anadyomene, completed forty years later, and exhibited in 1855. These works were followed by some of his best portraits, that of Monsieur Bochet, and that of Madame la Comtesse de Tournon, mother of the prefect of the department of the Tiber. In 1811 he finished Jupiter and Thetis, an immense canvas, Romulus's victory over Acron, and Virgil reading the Aeneid. These were followed by the Betrothal of Raphael, a small painting, now lost, executed for Queen Maria Carolina of Naples; Don Pedro of Toledo Kissing the Sword of Henry IV, exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1814, together with the Sistine Chapel and the Grande odalisque. In 1815 Ingres executed Raphael and the Fornarina in 1816 Aretino and the envoy of Charles V, and Aretino and Tintoretto; in 1817 the Death of Leonardo and Henry IV playing with his children, both of which works were commissions from the Comte de Blacas, then ambassador of France to the Holy See. Roger and Angelique and Francesca di Rimini, were completed in 1819, and followed in 1820 by Christ giving the keys to Peter.

Grande odalisque, painted 1814, Louvre. The texture of the fabric and the smooth skin of the girl are painted in intricate detail. The elongated features of the subject — who has apparently too many vertebrae — are reminiscent of old Mannerist painters. Ingres was searching for the pure form of his models.In 1815, also, Ingres had made many projects for treating a subject from the life of the celebrated Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alva, a commission from the family, but a loathing for "cet horrible homme" grew upon him, and finally he abandoned the task and entered in his diary, "J'etais forcé par la necessité de peindre un pareil tableau; Dieu a voulu qu'il reste en ebauche." ("I was forced by need to paint such a painting; God wanted it to remain a sketch.")

During all these years Ingres's reputation in France did not increase. The interest which his Sistine Chapel had aroused at the Salon of 1814 soon died away; not only was the public indifferent, but amongst other artists Ingres found scant recognition. The strict classicists looked upon him as a renegade, and strangely enough Eugène Delacroix and other pupils of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, the leaders of that romantic movement for which Ingres, throughout his long life, always expressed the deepest abhorrence, alone seem to have been sensible of his merits. The weight of poverty, too, was hard to bear. In 1813 Ingres had married; his marriage had been arranged for him with a young woman who came in a business-like way from Montauban, on the strength of the representations of her friends in Rome. Madame Ingres acquired a faith in her husband which enabled her to combat with courage and patience the difficulties which beset their common existence, and which were increased by their removal to Florence. There Bartolini, an old friend, had hoped that Ingres might have materially bettered his position. This expectation were disappointed. The good offices of Bartolini, and of one or two other persons, could only alleviate the miseries of this stay in a town where Ingres was all but deprived of the means of gaining daily bread by the making of those small portraits for the execution of which, in Rome, his pencil had been constantly in request.

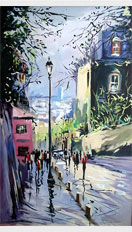

The spring, 1856Before his departure he had, however, been commissioned to paint for Monsieur de Pastoret the Entry of Charles V into Paris, and de Pastoret now obtained an order for Ingres from the Administration of Fine Arts; he was directed to treat the Vow of Louis XIII for the cathedral of Montauban. This work, exhibited at the Salon of 1824, met with universal approbation: even those sworn to observe the unadulterated precepts of David found only admiration for the Vow of Louis XIII On his return Ingres was received at Montauban with enthusiastic homage, and found himself celebrated throughout France. In the following year (1825) he was elected to the Institute, and his fame was further extended in 1826 by the publication of Sudre's lithograph of the Grande Odalisque, which, having been scorned by artists and critics alike in 1819, now became widely popular.

A second commission from the government called forth the Apotheosis of Homer. From 1826 to 1834 the studio of Ingres was thronged, as once had been thronged the studio of David, and he was a recognized chef d'école. Whilst he taught with authority and wisdom, he steadily worked; and when in 1834 he produced his great canvas of the Martyrdom of Saint Symphorien (cathedral of Autun; lithographed by Trichot-Garneri), it was with angry disgust and resentment that he found his work received with the same doubt and indifference, if not the same hostility, as had met his earlier ventures. Ingres resolved to work no longer for the public, and gladly availed himself of the opportunity to return to Rome, as director of the École de France, in the room of Horace Vernet. There he executed The virgin of the host, Stratonice, Portrait of Luigi Cherubini, and the Little Odalisque for Monsieur Marcotte, the faithful admirer for whom, in 1814, Ingres had painted the Sistine Chapel.

The Stratonice, executed for Louis-Philippe, duc d'Orléans, had been exhibited at the Palais Royal for several days after its arrival in France, and the beauty of the composition produced so favourable an impression that, on his return to Paris in 1841, Ingres found himself received with all the deference that he felt to be his due. A portrait of the purchaser of Stratonice was one of the first works executed after his return; and Ingres shortly afterwards began the decorations of the great hall in the Chateau de Dampierre, which, unfortunately for the reputation of the painter, were begun with an ardour which gradually slackened, until in 1849 Ingres, having been further discouraged by the loss of his faithful and courageous wife, abandoned all hope of their completion, and the contract with the duc de Luynes was finally cancelled.

A minor work, Jupiter and Antiope, marks the year 1851, but Ingres's next considerable undertaking (1853) was the Apotheosis of Napoleon I, painted for the ceiling of a hall in the Hotel de Ville, Paris; Joan of Arc appeared in 1854; and in 1855 Ingres consented to rescind the resolution, more or less strictly kept since 1834, in favour of the International Exhibition, where a room was reserved for his works. Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte, president of the jury, proposed an exceptional recompense for their author, and obtained from emperor Napoleon III of France Ingres's nomination as grand officer of the Legion of Honour. With renewed confidence Ingres now took up and completed one of his most charming productions, The spring, a figure of which he had painted the torso in 1823, and which seen with other works in London in 1862 there renewed the general sentiment of admiration, and procured him, from the imperial government, the dignity of senator.

The Turkish bath, 1862After the completion of The spring, the principal works produced by Ingres were with one or two exceptions (Molière and Louis XIV, 1858; The Turkish bath 1859), were of a religious character. The virgin of the adoption, 1858 (painted for Mademoiselle Roland-Gosselin), was followed by The virgin crowned (painted for Madame la Baronne de Larinthie) and The virgin with child. In 1859 these were followed by repetitions of The virgin of the host; and in 1862 Ingres completed Christ and the doctors, a work commissioned many years before by Queen Marie Amalie for the chapel of Bizy.

On 17 January 1867 Ingres died in his eighty-eighth year, having preserved his faculties to the last. He was interred in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France.

Work

Odalisque with a Slave, 1840It is to be noted that the Saint Symphorien

exhibited in 1834 closes the list of the works on which his reputation

will chiefly rest; for The spring, which at first sight seems to

be an exception, was painted, all but the head and the extremities,

in 1821; and from those who knew the work well in its incomplete

state we learn that the after-painting, necessary to fuse new and

old, lacked the vigour, the precision, and the something like touch

which distinguished the original execution of the torso.

Roger and Angelique, 1819, portrays an episode from Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto.Touch was not, indeed, at any time a means of expression on which Ingres seriously calculated; his constant employment of local tint, in mass but faintly modelled in light by half tones, forbade recourse to the shifting effects of colour and light on which the Romantic school depended in indicating those fleeting aspects of things which they rejoiced to put on canvas; their methods would have disturbed the calculations of an art wholly based on form and line. Except in his Sistine Chapel, and one or two slighter pieces, Ingres kept himself free from any preoccupation as to depth and force of colour and tone; driven, probably by the excesses of the Romantic movement into an attitude of stricter protest. "Ce que l'on sait," he would repeat, "il faut le savoir l'épée à la main." ("This is what I know: one must know the sword in the hand.") Ingres left himself therefore, in dealing with crowded compositions, such as the Apotheosis of Homer and the Martyrdom of Saint Symphorien, without the means of producing the necessary unity of effect which had been employed in due measure, as the Stanze of the Vatican bear witness, by the very master (Raphael) whom he most deeply reverenced. Thus it came to pass that in subjects of one or two figures Ingres showed to the greatest advantage: in Oedipus, in the Girl after bathing, the Odalisque and The spring, subjects only animated by the consciousness of perfect physical well-being, we find Ingres at his best. One hesitates to put Roger and Angelique upon this list, for though the female figure shows the finest qualities of Ingres's work, deep study of nature in her purest forms, perfect sincerity of intention and power of mastering an ideal conception; yet side by side with these the effigy of Roger on his hippogriff bears witness that from the passionless point of view, which was Ingres's birthright, the weird creatures of the fancy cannot be seen.