Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yur'yevich Lermontov, (October 15, 1814–July 27, 1841), a Russian Romantic writer and poet, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", was the most important presence in the Russian poetry from Alexander Pushkin's death until his own four years later, at the age of 26 - like Pushkin, the casualty of a duel. In one of his best-known poems, written on January 1, 1840 he described his intonations as "iron verse steeped in bitterness and hatred."

Early life

Lermontov was born in Moscow to a respectable family of the Tula government, and grew up in the village of Tarkhany (in the Penza government), which now preserves his remains. His family traced descent from the Scottish Learmounts, one of whom settled in Russia in the early 17th century, during the reign of Michael Fedorovich Romanov.

The family did not fare well for very long, however, and Lermontov's father, Yuri Lermontov, like his father before him, entered military service. Having moved up the ranks of captain, he married the sixteen year old Mariya Arsenyeva, to the great dismay of her mother, Elizabeth Alekseevna. A year later after the marriage, on the night of October 3rd, 1814, Mariya Arsenieva gave birth to Mikhail Lermontov. Soon after his birth, some discord between Lermontov's father and grandmother had erupted, and being unable to bear it, Mariya Arsenieva fell ill and died in 1817. After her daughter's death, Elizabeth Alekseevna devoted all her care and attention to little Lermontov and his education, all the time fearing that his father might sooner or later run off with him. Either because of this pampering or continuing family tension or both, Lermontov developed a fearful and arrogant temper and love for destruction, which he proceeded to take out on the servants and the bushes in his grandmother's garden.

As a young child Lermontov listened to stories about the Volga rogues, and his imagination was enraptured by their miraculous bravery and sulking, feral abodes. Unfortunately at ten years of age he fell sick, and to soothe his illness, Elizabeth Alekseevna took him to see Caucasus. There, young Lermontov for the first time loved- a girl he would later describe as having golden hair and a "pair of angelic eyes".

The intellectual atmosphere which he breathed in his youth differed little from that in which Pushkin had grown up, though the domination of French had begun to give way before the fancy for English, and Lamartine shared his popularity with Byron. In his early childhood Lermontov was educated by a certain Frenchman named Gendrot; but Gendrot was a poor pedagogue, and Elizabeth Alekseevna decided to take Lermontov to Moscow to prepare him better for the gymnasium. In Moscow, Lermontov was introduced to Goethe and Schiller by a German pedagogue, Levy, and a short time after, in 1828, he entered the gymnasium. He showed himself to be an incredibly talented student, once completely stealing the show at an exam by, first, impeccably reciting some poetry, and second, successfully performing a violin piece. At the gimnasium he also became acquainted with the poetry of Pushkin and Zhukovsky, and one of his friends, Catherine Hvostovaya, later described him as "married to a hefty volume of Byron". This friend had at one time been an object of Lermontov's affection, and to her he dedicated some of his earliest poems, one of the most remarkable ones being (tr?). At that time, together with Lermontov's poetic passion, there also awoke an inclination for poisonous wit and cruel and sardonic humor. His ability to draw caricatures was matched by his ability to shoot someone down with a well aimed epigram or nickname.

From the academic gymnasium Lermontov passed on, in the August of 1830, to the Moscow University. That same summer the final, tragic act of the family discord played out. Having been struck deep by his son's alienation, Yuri Lermontov leaves the Arseniev house for good, only to die a short time later. His father's death on such a note was a terrible loss for Lermontov, as is evidenced by a few of his poems: "Forgive me, Will we Meet Again?" and "The Terrible Fate of Father and Son".

Lermontov's career at the University was very abrupt. While there, he was remembered for his aloofness and arrogant disposition; he attended the lectures rather faithfully, often reading a book in the corner of the auditorium, but rarely took part in student life. What brought his time at the University to an end was a prank a group of students pulled against the obnoxious professor Malov. Once, when the professor commenced the lecture with his favorite phrase, "the man, who," a group of students that had already gathered there from various departments, started to applaud and yell: "Fora! Excellent!" At this, Malov coiled up, crawled off the podium, and quickly walked out onto the street, where the students followed and threw a pair of shoes after him. Lermontov, who had attended this "event", could have dearly paid for it, and thus, some consider this to be the reason for his departure.

The events at the University led Lermontov to seriously reconsider his career choice. From 1830 to 1834 he attended the school of cadets at Saint Petersburg, and in due course he became an officer in the guards. There Lermontov got a chance to show off his incredible strength and prankish character: he and another junker would tie steel ramrods, as if they were simple ropes, into knots, until they were caught at this task by General Schlippenbach. When he caught them, he yelled out, "What, are you kids, to pull pranks like these?" and since that time Lermontov would laugh:"What kids! to tie steel ramrods into knots!" All this time he was writing much poetry imitative of Pushkin and Byron. He also took a keen interest in Russian history and medieval epics, which would be reflected in the Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov, his long poem Borodino, poems addressed to the city of Moscow, and a series of popular ballads.

Fame and exile

To his own and the nation's anger at the loss of Pushkin (1837) the young soldier gave vent in a passionate poem addressed to the tsar, and the very voice which proclaimed that, if Russia took no vengeance on the assassin of her poet, no second poet would be given her, was itself an intimation that such a poet had come already. The poem all but accused the powerful "pillars" of Russian high society of complicity in Pushkin's murder. Without mincing words, it portrayed this society as a cabal of venal and venomous wretches "huddling about the Throne in a greedy throng", "the hangmen who kill liberty, genius, and glory" about to suffer the apocalyptic judgement of God. Cleaving the repressive atmosphere of 1830's Russia like a lightning bolt from a still sky, the poem had the power of Biblical prophecy, though the poet's contemporaries were often more likely to perceive it as the ravings of a madman.

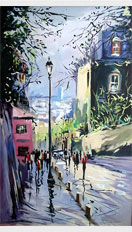

Lermontov took delight in painting mountain landscapesThe tsar, however, seems to have found more impertinence than inspiration in the address, for Lermontov was forthwith sent off to the Caucasus as an officer of dragoons. He had been in the Caucasus with his grandmother as a boy of ten, and he found himself at home by yet deeper sympathies than those of childish recollection. The stern and rocky virtues of the mountaineers against whom he had to fight, no less than the scenery of the rocks and of the mountains themselves, proved akin to his heart; the emperor had exiled him to his native land.

Lermontov visited Saint Petersburg in 1838 and 1839, and his indignant observations of the aristocratic milieu, wherein fashionable ladies welcomed him as a celebrity, occassioned his play Masquerade. Otherwise, his unreciprocated attachment to Varvara Lopukhina was recorded in the novel Princess Ligovskaya, which he never finished. His duel with a son of the French ambassador led to his being returned to the Caucasian army, where he distinguished himself in the hand-to-hand fighting near the Valerik River.

By 1839 he completed his only full-scale novel, A Hero of Our Time, which prophetically describes the duel in which he lost his life in July 1841. In this contest he had purposely selected the edge of a precipice, so that if either combatant was wounded so as to fall his fate should be sealed. Much of his best verse was posthumously discovered in his pocket-book.

Works

During his lifetime, Lermontov published only one slender collection of poems (1840). Three volumes, much mutilated by the censorship, were issued a year after his death. His short poems range from indignantly patriotic pieces like Fatherland to the pantheistic glorification of living nature (e.g., I Go Out to the Road Alone...) Lermontov's early verse has been accused of puerility, for, despite his dexterious command of the language, it usually appeals more to adolescents than to adults. But that typically Romantic air of disenchantment was an illusion of which he was too conscious himself. Quite unlike Shelley, with whom he is often compared, he attempted to analyse and bring to light the deepest reasons for this metaphysical discontent with society and himself (e.g., It's Boring and Sad...)

Mikhail Vrubel's illustration to the Demon (1890).Both patriotic and pantheistic veins in his poetry had incalculable repercussions throughout later Russian literature. Boris Pasternak, for instance, dedicated his 1917 poetic collection of signal importance to the memory of Lermontov's Demon. Such was the name of a long poem, featuring some of the most mellifluent lines in the language, which Lermontov rewrote upon a number of occassions, until his very death. The poem, which celebrates carnal passions of the "eternal spirit of atheism" to a "maid of mountains", was banned from publication for decades. Anton Rubinstein's lush opera on the same subject was also banned by censors who deemed it sacrilegious.