Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th century art movement, that began as a loose association of Paris-based artists who began publicly exhibiting their art in the 1860s. The name of the movement is derived from Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant). Critic Louis Leroy inadvertently coined the term in a satiric review published in Le Charivari.

The influence of Impressionist thought spread beyond the art world, leading to Impressionist music and Impressionist literature.

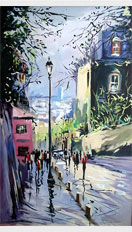

Characteristic of impressionist painting are visible brushstrokes, light colors, open composition, emphasis on light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, and unusual visual angles.

Impressionism also describes art done in this style, but outside of the late 19th century time period.

Overview

Radicals in their time, early impressionists broke the picture making rules of earlier generations. They captured a fresh and original vision that seemed strange and unfinished to their viewing public. Rejecting attempts to portray ideal beauty, the impressionists looked instead to beauty in candid day-to-day living. They painted "en plein air" (outdoors) rather than in a studio as was the custom, capturing the momentary and transient aspects of sunlight.

Impressionist paintings feature short, "broken" brush strokes of pure, untinted and unmixed pigments that give an appearance of spontaneity and vitality. The surfaces of the paintings are often textured with thick paint, a characteristic setting them apart from their predecessors in which smooth blending minimized the perception that one is looking at paint on canvas. Compositions are simplified and innovative, and the emphasis is on overall effect rather than upon details.

Beginnings

In an atmosphere of change as Emperor Napoleon III rebuilt Paris and waged war, the Académie des beaux-arts dominated the French art scene in the middle of the 19th century. Art at the time was considered a conservative enterprise whose innovations fell within the Académie's defined borders. The Académie set the standards for French painting.

In addition to dictating the content of paintings (historical and religious themes, and portraits were valued), the Académie commanded which techniques artists used. They valued somber, conservative colours. Refined images, mirroring reality when closely examined, were esteemed. The Académie encouraged artists to eliminate all traces of brush strokes — essentially isolating art from the artist's personality, emotions, and working techniques.

The Académie held an annual art show — Salon de Paris, and artists whose work displayed in the show won prizes and garnered commissions to create more art. Only art selected by the Académie jury exhibited in the show. The standards of the juries about suitable art for the salon reflected the values of the Académie.

The young artists painted in a lighter and brighter style than most of the generation before them, extending the realism style of Gustave Courbet, Winslow Homer and the Barbizon school. They submitted their art to the Salon, and the juries rejected the pieces. A core group of them, Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley, studied under Charles Gleyre. The three of them became friends and often painted together.

In 1863, the jury rejected The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe) by Édouard Manet primarily because it depicted a nude woman with two clothed men on a picnic. According to the jury nudes were acceptable in historical and allegorical paintings, but to show them in common settings was forbidden. Manet felt humiliated by the sharply worded rejection of the jury, which set off a firestorm among many French artists. Although Manet did not consider himself an impressionist, he led discussions at Café Guerbois where the impressionists gathered, and influenced the explorations of the artistic group.

After seeing the rejected works in 1863, Emperor Napoleon III decreed that the public be allowed to judge the work themselves, and the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Refused) was organized.

For years art critics rebuked the Salon des Refusés, and in 1874 the impressionists (though not yet known by the name) organized their own exhibition.

After seeing the show, critic Louis Leroy (an engraver, painter, and successful playwright), wrote a scathing review in the Le Charivari newspaper. Targeting a painting by a then obscure artist he titled his article, The Exhibition of the Impressionists. Leroy declared that Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant) by Claude Monet was at most a sketch and could hardly be termed a finished work.

Leroy wrote, in the form of a dialog between viewers,

Impression — I was certain of it. I was just telling myself

that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in

it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper

in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.

The term "impressionists" gained favor with the artists,

not as a term of derision, but as a badge of honor. The techniques

and standards within the movement varied, but the spirit of rebellion

and independence bound the movement together.

Impressionist techniques

Short, thick strokes of paint in a sketchy way, allowing the painter

to capture and emphasize the essence of the subject rather than

its details.

They left brush strokes on the canvas, adding a new dimension of

familiarity with the personality of the artist for the viewer to

enjoy.

Colours with as little pigment mixing as possible, allowing the

eye of the viewer to optically mix the colors as they looked at

the canvas, and providing a vibrant experience for the viewer.

Impressionists did not tint (mix with black) their colours in order

to obtain darker pigments. Instead, when the artists needed darker

shades, they mixed with complementary colours. (Black was used,

but only as a colour in its own right.)

They painted wet paint into the wet paint instead of waiting for

successive applications to dry, producing softer edges and intermingling

of color.

Impressionist avoided the use of thin paints to create glazes which

earlier artists built up carefully to produce effects. Rather, the

impressionists put paint down thickly and did not rely upon layering.

Impressionists discovered or emphasized aspects of the play of natural

light, including an acute awareness of how colours reflect from

object to object.

In outdoor paintings, they boldly painted shadows with the blue

of the sky as it reflected onto surfaces, giving a sense of freshness

and openness that was not captured in painting previously. (Blue

shadows on snow inspired the technique.)

They worked "en plein air" (outdoors)

Previous artists occasionally used these techniques, but impressionists

employed them constantly. Earlier examples are found in the works

of Frans Hals, Peter Paul Rubens, John Constable, Theodore Rousseau,

Gustave Courbet, Camille Corot, Eugene Boudin, and Eugène

Delacroix.

Impressionists took advantage of the mid-century introduction of premixed paints in tubes (resembling modern toothpaste tubes) which allowed artists to work more spontaneously both outdoors and indoors. Previously, each painter made their own paints by grinding and mixing dry pigment powders with linseed oil.

Content and composition

Even though, historically, painting was viewed as primarily a way to depict historical and religious subjects in a rather formal manner, painters portrayed everyday subjects. Many 17th century Dutch painters, like Jan Steen, focused on common subjects, but their works showed the influences of traditional composition in arrangement of the scene.

When impressionism began, there was interest among the artists in mundane subject matter, and a new method of capturing images became available. Photography was gaining popularity, and as cameras became more portable, photographs became more candid. Photography inspired impressionists to capture the moment, not only in the fleeting lights of a landscape, but in the day-to-day lives of people.

Photography and popular Japanese art prints (Japonism) combined to introduce to impressionists odd "snapshot" angles, and unconventional compositions.

Edgar Degas' The Dance Class (La classe de danse) shows both influences. A dancer is caught in adjusting her costume, and the lower right quadrant of the picture contains empty floor space.