Modernism

Modernism in the cultural historical sense is generally defined as the new artistic and literary styles that emerged in the decades before 1914 as artists rebelled against the late 19th century norms of depiction and literary form, in an attempt to present what they regarded as an emotionally truer picture of how people really feel and think.

Some divide the 20th century into modern and post-modern periods, where as others see them as two parts of the same larger period. This article will focus on the movement that grew out of the late 19th and early 20th century, while Post-modernism has its own article.

Historical outline

"Just as the ancients drew the inspiration for their arts from

the world of nature...so we should draw ours from the mechanized

environment we have created."

—Antonio Sant'Elia Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (1914)

The modernist movement emerged in the mid-19th century in France

and was rooted in the idea that "traditional" forms of

art, literature, social organization and daily life had become outdated,

and that it was therefore essential to sweep them aside and reinvent

culture. It encouraged the idea of re-examination of every aspect

of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding

that which was "holding back" progress, and replacing

it with new, and therefore better, ways of reaching the same end.

In essence, the Modern Movement argued that the new realities of

the 20th century were permanent and imminent, and that people should

adapt to their world view to accept that what was new was also good

and beautiful.

Precursors to modernism

The first half of the 19th century for Europe was marked by a series of turbulent wars and revolutions, which gradually formed into a series of ideas and doctrines now identified as Romanticism, which focused on individual subjective experience, the supremacy of "Nature" as the standard subject for art, revolutionary or radical extensions of expression, and individual liberty. By mid-century, however, a synthesis of these ideas, and stable governing forms had emerged. Called by various names, this synthesis was rooted in the idea that what was "real" dominated over what was subjective. It is exemplified by Otto von Bismarck's realpolitik, philosophical ideas such as positivism and cultural norms now described by the word Victorian.

Central to this synthesis, however, was the importance of institutions, common assumptions and frames of reference. These drew their support from religious norms found in Christianity, scientific norms found in classical physics and doctrines which asserted that depiction of the basic external reality from an objective standpoint was possible. Cultural critics and historians label this set of doctrines Realism, though this term is not universal. In philosophy, the rationalist and positivist movements established a primacy of reason and system.

Against the current were a series of ideas. Some were direct continuations of Romantic schools of thought. Notable were the agrarian and revivalist movements in plastic arts and poetry (e.g. the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the philosopher John Ruskin). Rationalism also drew responses from the anti-rationalists in philosophy. In particular, Hegel's dialectic view of civilization and history drew responses from Friedrich Nietzsche and Søren Kierkegaard, who was a major precursor to Existentialism. All of these separate reactions together, however, began to be seen as offering a challenge to any comfortable ideas of certainty derived by civilization, history, or pure reason.

From the 1870s onwards, the views that history and civilization were inherently progressive, and that progress was inherently amicable, were increasingly called into question. Writers like Wagner and Ibsen had been reviled for their own critiques of contemporary civilisation, and warned that increasing "progress" would lead to increasing isolation and the creation of individuals detached from social norms and their fellow men. Increasingly, it began to be argued not merely that the values of the artist and those of society were different, but that society was antithetical to progress itself, and could not move forward in its present form. Moreover, there were new views of philosophy that called into question the previous optimism. The work of Schopenhauer was labelled "pessimistic" for its idea of the "negation of the will", an idea that would be both rejected and incorporated by later thinkers such as Nietzsche.

Two of the most disruptive thinkers of the period were, in biology Charles Darwin, and in political science Karl Marx. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection undermined religious certainty of the general public, and the sense of human uniqueness of the intelligentsia. The notion that human beings were driven by the same impulses as "lower animals" proved to be difficult to reconcile with the idea of an ennobling spirituality. Karl Marx seemed to present a political version of the same problem: that problems with the economic order were not transient, the result of specific wrong doers or temporary conditions, but were fundamentally contradictions within the "capitalist" system. Both thinkers would spawn defenders and schools of thought that would become decisive in establishing modernism.

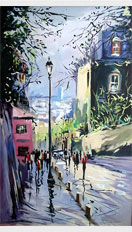

Separately, in the arts and letters, two ideas originating in France would have particular impact. The first was Impressionism, a school of painting that initially focused on work done, not in studios, but outdoors (en plein air). They argued that human beings do not see objects, but instead see light itself. The school gathered adherents, and despite deep internal divisions among its leading practitioners, became increasingly influential. Initially rejected from the most important commercial show of the time — the government sponsored Paris Salon — the art was shown at the Salon des Refusés, created by Emperor Napoleon III to display all of the paintings rejected by the Paris Salon. While most were in standard styles, but by inferior artists, the work of Manet attracted tremendous attention, and opened commercial doors to the movement.

The second school was Symbolism, marked by a belief that language is expressly symbolic in its nature, and that poetry and writing should follow whichever connection the sheer sound and texture of the words create. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé would be of particular importance to what would occur afterwards.

At the same time social, political, and economic forces were at work that would eventually be used as the basis to argue for a radically different kind of art and thinking.

Chief among these was industrialization, which produced buildings such as the Eiffel Tower that broke all previous limitations on how tall man-made objects could be, and at the same time offered a radically different environment in urban life. The miseries of industrial urbanity, and the possibilities created by scientific examination of subjects would be crucial in the series of changes that would shake European civilization, which, at that point, regarded itself as having a continuous and progressive line of development from the Renaissance.

The breadth of the changes can be seen in how many disciplines are described, in their pre-20th century form, as being "classical", including physics, economics, and arts such as ballet.

The beginning of modernism 1890–1910

Clement Greenberg wrote 'What can be safely called Modernism emerged in the middle of the last century. And rather locally, in France, with Baudelaire in literature and Manet in painting, and maybe with Flaubert, too, in prose fiction. (It was a while later, and not so locally, that Modernism appeared in music and architecture, but it was in France again that it appeared first in sculpture. Outside France later still, it entered the dance.) The "avant-garde" was what Modernism was called at first, but this term has become a good deal compromised by now as well as remaining misleading. Contrary to the common notion, Modernism or the avant-garde didn't make its entrance by breaking with the past. Far from it. Nor did it have such a thing as a program, nor has it really ever had one -- again, contrary to the common notion. Nor was it an affair of ideas or theories or ideology. It's been in the nature, rather, of an attitude and an orientation: an attitude and orientation to standards and levels: standards and levels of aesthetic quality in the first and also the last place. And where did the Modernists get their standards and levels from? From the past, that is, the best of the past. But not so much from particular models in the past -- though from these too -- as from a generalized feeling and apprehending, a kind of distilling and extracting of aesthetic quality as shown by the best of the past. And it wasn't a question of imitating but one of emulating -- just as it had been for the Renaissance with respect to antiquity. It's true that Baudelaire and Manet talked much more about having to be modern, about reflecting life in their time, than about matching the best of the past. But the need and the ambition to do so show through in what they actually did, and in enough of what they were recorded as saying. Being modern was a means of living up to the past'.

Beginning in the 1890s and with increasing force afterwards, a strand of thinking began to assert that it was necessary to push aside previous norms entirely, and instead of merely revising past knowledge in light of current techniques, it would be necessary to make more thorough changes. The movement in art paralleled such developments as the Theory of Relativity in physics; the increasing integration of internal combustion and industrialization; and the rise of social sciences in public policy. In the first fifteen years of the twentieth century a series of writers, thinkers, and artists made the break with traditional means of organizing literature, painting, and music - again, in parallel to the change in organizational methods in other fields. The argument was that if the nature of reality itself was in question, and the restrictions which, it was felt, had been in place around human activity were falling, then art too, would have to radically change.

As vividly Sigmund Freud offered a view of subjective states that involved a unconscious mind full of primal impulses and counterbalancing restrictions, and Carl Jung would combine Freud's doctrine of the unconscious with a belief in natural essence to stipulate a collective unconscious that was full of basic typologies that the conscious mind fought or embraced. This attacked the idea that people's impulses towards breaking social norms were the product of being childish or ignorant, and were instead essential to the nature of the human animal, and the ideas of Darwin had introduced the idea of "man, the animal" to the public mind.

At the same time, and in nearly the same place as Freud, Friedrich Nietzsche championed a process philosophy, in which processes and forces, specifically the 'will to power', were more important than facts or things. Similarly the writings of Henri Bergson became increasingly influential, who also championed the vital 'life force' over static conceptions of reality. What united all these writers was a romantic distrust of the Victorian positivism and certainty. Instead they championed, or, in case of Freud, attempted to explain, irrational thought processes through the lens of rationality and holism. This was connected with a general search to culminate the century long trend to thinking in terms of holistic ideas, which would include an increased interest in the occult, and "the vital force".

Out of this collision of ideals from Romanticism, and an attempt to find a way for knowledge to explain that which was as yet unknown, came the first wave of works, which, while their authors considered them extensions of existing trends in art, broke the implicit contract that artists were the interpreters and representatives of bourgeoise culture and ideas. The landmarks include Arnold Schoenberg's atonal ending to his Second String Quartet in 1906, the abstract paintings of Wassily Kandinsky starting in 1903 and culminating with the founding of the Blue Rider group in Munich, and the rise of cubism from the work of Picasso and Georges Braque in 1908.

Powerfully influential in this wave of modernity were the theories of Freud, who argued that the mind had a basic and fundamental structure, and that subjective experience was based on the interplay of the parts of the mind. All subjective reality was based, according to Freud's ideas, on the play of basic drives and instincts, through which the outside world was perceived. This represented a break with the past, in that previously it was believed that external and absolute reality could impress itself on an individual, as, for example, in John Locke's tabula rasa doctrine.

However, the modern movement was not merely defined by its avant-garde but also by a reforming trend within previous artistic norms. This search for simplification of diction was found in the work of Joseph Conrad. The pressures of communication, transportation and more rapid scientific development began placing a premium on architectural styles which were cheaper to build and less ornamented, and on writing which was shorter, clearer, and easier to read. The rise of cinema and "moving pictures" in the first decade of the twentieth century gave the modern movement an art form which was uniquely its own, and again, created a direct connection between the perceived need to extend the "progressive" tradition of the late nineteenth century, even if this conflicted with then established norms.

This wave of the modern movement broke with the past in the first decade of the twentieth century, and tried to redefine various artforms in a radical manner. Leading lights within the literary wing of this movement (or, rather, these movements) include Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Valery, D.H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, William Faulkner, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, Max Jacob, Paul Reverdy, Joseph Conrad, Marcel Proust, Louis Aragon, Tristan Tzara, Jean Cocteau, Paul Eluard, Gertrude Stein, Wyndham Lewis, H.D., Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, Robert Walser, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Federico Garcia Lorca, Rafael Alberti, and Franz Kafka. Composers such as Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Poulenc represent modernism in music. Artists such as Gustav Klimt, Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, and the Surrealists represent the visual arts, while architects and designers such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe brought modernist ideas into everyday urban life. Several figures outside of artistic modernism were influenced by artistic ideas; for example, John Maynard Keynes was friends with Woolf and other writers of the Bloomsbury group.

The explosion of modernism 1910–1930

On the eve of World War I, a growing tension and unease with the social order began to break through - seen in the Russian Revolution of 1905, the increasing agitation of "radical" parties, and an increasing number of works which either radically simplified or rejected previous practice. In 1913, famed Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, working for Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, composed Rite of Spring for a ballet that depicted human sacrifice, and young painters such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse had only recently begun causing a shock with their rejection of traditional perspective as the means of structuring paintings - a step that the Impressionists, nor even Cézanne, had not taken.

This development began to give a new meaning to what was termed 'Modernism'. At its core was the embracing of disruption, and a rejection of, or movement beyond, simple Realism in literature and art, and the rejection of, or dramatic alteration of, tonality in music. In the 19th century, artists had tended to believe in 'progress', though what that word entailed varied dramatically, and the importance of the artist's contributing positively to the values of society. So, for example, writers like Dickens and Tolstoy, painters like Turner, and musicians like Brahms were not 'radicals' or 'Bohemians', but were instead valued members of society who produced art that added to society, even if it was, at times, critiquing less desirable aspects of it. Modernism, while it was still "progressive" increasingly saw traditional forms and traditional social arrangements as hindering progress, and therefore the artist was recast as a revolutionary, overthrowing rather than enlightening.

An example of this trend was to be found in Futurism. In 1909, a manifesto was published in the newspaper Le Figaro, and rapidly a group of painters (Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini) co-signed The Manifesto of Futurist Painting. Such manifestos were modelled on the famous "Communist Manifesto" of the previous century, and were meant to provoke and gather followers while they put forward principles and ideas. However, Futurism was strongly influenced by Bergson and Nietzsche, and it should be seen as part of the general trend of Modernist rationalization of disruption.

It must be stressed that Modernist philosophy and art were still viewed as being part, and only a part, of the larger social movement. Artists such as Klimt, Paul Cezanne and Mahler and Richard Strauss were "the terrible moderns" - those farther to the avant-garde were more heard of, than heard. Polemics in favour of geometric or purely abstract painting were largely confined to 'little magazines' (like The New Age in the UK) with tiny circulations. Modernist primitivism and pessimism was controversial but was not seen as representative of the Edwardian mainstream, which was more inclined towards a Victorian faith in progress and liberal optimism.

However, World War I and its subsequent events were the cataclysmic disruptions that late 19th century artists such as Brahms had worried about, and avant-gardists had embraced.

First, the fantastic failure of the previous status quo seemed self-evident to a generation that had seen millions die fighting over scraps of earth - prior to the war, it had been argued that no one would fight such a war, since the cost was too high. Second, the introduction of a machine age into life seemed obvious - machine warfare became a touchstone of the ultimate reality. Finally, the immensely traumatic nature of the experience made both critical and subjective strands of the modern movement basic assumptions: Realism seemed to be bankrupt when faced with the fundamentally fantastic nature of trench warfare - as exemplified by books such as Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front. Moreover, the view that Mankind was making slow and steady moral progress came to seem ridiculous in the face of the senseless slaughter of the Great War. The First World War, at once, fused the harshly mechanical geometric rationality of technology with the nightmarish irrationality of myth.

Thus in the 1920s, and increasingly after, modernism, which had been such a minority taste before the war, came to define the age. There was a subtle, but important, shift from the earlier phase: in the beginning the movement was undertaken by individuals who were part of the establishment, or wished to join the establishment. However, increasingly, the mood began to shift towards a replacement of the older hierarchy with one based on new ideas, norms, and methods. Modernism was seen in Europe in such critical movements as Dada, and then in constructive movements such as Surrealism, as well as in smaller movements such as the Bloomsbury Group. Each of these "modernisms", as some observers labelled them at the time, stressed new methods to produce new results. Again, Impressionism was a precursor: breaking with the idea of national schools, artists and writers adopted ideas of international movements. Surrealism, Cubism, Bauhaus, and Leninism are all examples of movements that rapidly found adopters far beyond their original geographic base.

Exhibitions, theatre, cinema, books and buildings all served to cement in the public view the perception that the world was changing - and this often met with hostile resistance. Paintings were spat upon, riots organized at the opening of works, and some political figures even denounced modernism as being connected with immorality. At the same time, the 1920s were known as the "Jazz Age", and there was a public embrace of the advancements of mechanization: cars, air travel and the telephone. The assertion of Modernists was that these advances required people to change, not merely their habits, but their fundamental aesthetic sense.

By 1930, modernism had won a place in the establishment, including the political and artistic establishment.

Ironically, by the time it was being accepted, Modernism itself had changed. There was a general reaction in the 1920s against the pre-1918 Modernism, which emphasised its continuity with a past even as it rebelled against it, and against the aspects of that period, which seemed excessively mannered, irrational, and emotionalistic. The post-World War period, at first, veered either to systematization or nihilism and had, as perhaps its most paradigmatic movement, Dada.

Since both rationality and irrationality are present to varying degrees in all large movements, some writers attacked the madness of the new Modernism, while, at the same time, others described it as soulless and mechanistic. Modernists, in turn, attacked the madness of hurling millions of young men into the hell of war, and the falseness of artistic norms that could not depict the emotional reality of life in the 20th century.

The rationalistic side of modernism was a move back towards control, self-restraint, and an urge to re-engage with society. Some influences came from Machine Age thought and the idolization of technology. Examples of this approach include Stravinsky's neoclassical style of composition, the "International style" of Bauhaus, Schoenberg's atonality, the New Objectivity in German painting. At the same time, the desire to turn social critique into persuasive counter-order found expression in the beginnings of econometrics, and the rise of societies to reform nations along scientific, and often socialistic, lines. The victories of the Russian Revolution, with its emphasis, at least in words, on both humane life and rational planning, came to be taken by many as an example of the maxim "I have seen the future, and it works".

However, it must be remembered that these concepts and movements were often in competition with each other, and even in direct conflict. Within modernity there were disputes about the importance of the public, the relationship of art to audience, and the role of art in society. Rather than a lockstep, organized unity, it is better to see modernism as taking a series of responses to the situation as it was understood, and the attempt to wrestle universal principles from it. In the end science and scientific rationality, often taking models from the 18th Century Enlightenment, came to be seen as the source of logic and stability, while the basic primitive sexual and unconscious drives, along with the seemingly counter-intuitive workings of the new machine age, were taken as the basic emotional substance. From these two poles, no matter how seemingly incompatible, modernists began to fashion a complete worldview that could encompass every aspect of life, and express "everything from a scream to a chuckle".

Modernism's second generation (1930-1945)

By 1930, Modernism had entered popular culture with "The Jazz Age" and the increasing urbanization of populations, it had begun making systematic challenges to previous art and ideas, and was beginning to be looked to as the source for ideas to deal with the host of challenges faced in that particular historical moment. Modernism was, by this point, increasingly, represented in academia and was developing a self-conscious theory of its own importance. The Modernism of the 1930's then increasingly begins to focus on the realities of there being a popular culture which was not derived from high culture, but instead from its own realities, particularly of mass production. Modern ideas in art were also increasingly used in commercials and logos. The famous London Underground logo is an early example of the need for clear, easily recognizable and memorable visual symbols.

Another strong influence at this time was Marxism. After the generally primitivistic/irrationalist aspect of pre-World War One Modernism, which for many modernists precluded any attachment to merely political solutions, and the neoclassicism of the 1920s, as represented most famously by T.S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky - which rejected popular solutions to modern problems - the rise of Fascism, the Great Depression, and the march to war helped to radicalise a generation. The Russian Revolution was the catalyst to fuse political radicalism and utopianism, with more expressly political stances. Bertolt Brecht, Auden, and the philosophers Gramsci and Walter Benjamin are perhaps the most famous examplers of this Modernist Marxism. This move to the radical left, however, was neither universal, nor definitional. There is no particular reason to associate Modernism, fundamentally, with 'the left' and, in fact, many Modernists were explicitly of 'the right' (for example, Wyndham Lewis, W.B. Yeats, Arnold Schoenberg, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and many others).

One of the most visible changes of this period is the adoption of objects of modern production into daily life, electricity, the telephone, the automobile - and the need to work with them, repair them and live with them - created the need for new forms of manners, and social life. The kind of disruptive moment which only a few knew in the 1880's, became a common occurrence. The kind of speed of communication reserved for the stock brokers of 1890, became part of family life. Modernism as leading to social organization would produce inquiries into sex and the basic bondings of the nuclear, rather than extended, family. The Freudian tensions of infantile sexuality and the raising of children became more intense, because people had fewer children, and therefore a more specific relationship with each child: the theoretical, again, became the practical and even popular.

Modernism after the Second World War (1945-)

People often draw the lessons from history that they feel others should have learnt from experience, and the post-world war modernist experience is no exception. Nazi Germany was depicted as "the last charge Romanticism had in its belly", and the product of irrational attachment to the state. The shattering of Europe swept away many of the traditional forms and lifestyles which had been arguing against the adoption of a mechanised economy, and there was such a vast need of rebuilding, that everything had to be made new.

This period is often described as "High Modernism", and on the one hand it lead to artists exploring the most extended, some would say extreme, consequences of modernist ideas - for example serialism and abstract expressionism, and at the same time, modernist design - in consumer goods, architecture, clothing and furnishings, became the norm. The top hats, dresses and frills of another age were tossed aside, or used only as high costume. The expansion of rail and road networks, the pouring of labor into cities from the country-side, and the vast building programs necessitated by the need to command and control the new economy, meant that the societies of Europe, America and Japan were thrust into the modern, and modernist, world.

The collision between popular sensibility and rarefied ideas became one of the most contentious, and extended, debates within modernism. The conflict, always latent, became acute, as, on one hand, the need for ever more specialised elites and ever more specialised knowledge pushed towards the "pure" forms of modernism, while at the same time mass production, broadcasting and organisation lead to the creation of popular culture which, while it made reference to the imagined Victorian way of life, was as rooted in new ideas as the most esoteric of poems.

Modernism itself began to face a series of crisis points as the unquestioned assumption that artistic and philosophical progress was mirrored and equivalent to technical progress became more problematic for more and more artists. One example from music is in the serialist music of Pierre Boulez - where he began to feel that pure parameterisation was not enough to produce the variety of sound which was pleasing. His correspondent, and some time rival, John Cage argued that if pure serial music sounded random to people, why not just use random process to create music? Another example from painting can be seen at the boundary of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism in painting - if the only thing that mattered was the presentation, why cover a canvas with so much.

For some artists these challenges were best met by reviving, renewing or expanding the precepts of Modernism as a continuing revolution, that the new environment, having produced more liberation was an invitation to yet further artistic "experimentation", as a modernist would call it, and more direct methods of creation. Examples of this would be the work of Willem de Kooning and that of Fuller Potter[1], who as painters sought more and more expressionistic means of presentation. For others, it meant the abandoning of the "pressure" that modernism seemed to impose on them, for example the change in styles of composer Lukas Foss. For other young artists, there was no conflict, merely a permission to act in whatever manner seemed most conducive to their inner sense of expression - exemplified by Andy Warhol.

The views on what this meant, and mean, differ widely. For some, the relaxation of progress and rationality represent a betrayal of modernism, for others, for whom modern and contemporary are close synonyms, it was merely modernism by other means. This division, between modern as meaning a particular way of responding to conditions and those who feel that modernism is merely "relevant to the present", has been seen in arguments over what music to include in programs, what art to show at galleries and where to draw lines in history.

Modernism's goals

any modernists believed that by rejecting tradition they could discover radically new ways of making art. Arnold Schoenberg believed that by ignoring traditional tonal harmony, the hierarchical system of organizing works of music which had guided music making for at least a century and a half, and perhaps longer, he had discovered a wholly new way of organizing sound, based in the use of twelve-note rows (See Twelve-tone technique). This led to what is known as serial music by the post-war period. Abstract artists, taking as their examples the Impressionists, as well as Paul Cézanne and Edvard Munch, began with the assumption that color and shape formed the essential characteristics of art, not the depiction of the natural world. Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich all believed in redefining art as the arrangement of pure colour. The use of photography, which had rendered much of the representational function of visual art obsolete, strongly affected this particular aspect of modernism. However, these artists also believed that by rejecting the depiction of material objects they helped art move from a materialist to a spiritualist phase of development.

Other modernists, especially those involved in design, had more pragmatic views. Modernist architects and designers believed that new technology rendered old styles of building obsolete. Le Corbusier (born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret) thought that buildings should function as "machines for living in", analogous to cars, which he saw as machines for travelling in. Just as cars had replaced the horse, so modernist design should reject the old styles and structures inherited from Ancient Greece or from the Middle Ages. Following this machine aesthetic, modernist designers typically reject decorative motifs in design, preferring to emphasise the materials used and pure geometrical forms. The skyscraper, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building in New York (1956 – 1958), became the archetypal modernist building. Modernist design of houses and furniture also typically emphasised simplicity and clarity of form, open-plan interiors, and the absence of clutter. Modernism reversed the 19th century relationship of public and private: in the 19th century, public buildings were horizontally expansive for a variety of technical reasons, and private buildings emphasized verticality - to fit more private space on more and more limited land. Where as in the 20th century, public buildings became vertically oriented, and private buildings became organized horizontally. Many aspects of modernist design still persist within the mainstream of contemporary architecture today, though its previous dogmatism has given way to a more playful use of decoration, historical quotation, and spatial drama.

In other arts such pragmatic considerations were less important. In literature and visual art some modernists sought to defy expectations mainly in order to make their art more vivid, or to force the audience to take the trouble to question their own preconceptions. This aspect of modernism has often seemed a reaction to consumer culture, which developed in Europe and North America in the late 19th century. Whereas most manufacturers try to make products that will be marketable by appealing to preferences and prejudices, high modernists rejected such consumerist attitudes in order to undermine conventional thinking. The art critic Clement Greenberg expounded this theory of modernism in his essay Avant Garde and Kitsch. Greenberg labelled the products of consumer culture "kitsch", because their design aimed simply to have maximum appeal, with any difficult features removed. For Greenberg, modernism thus formed a reaction against the development of such examples of modern consumer culture as commercial popular music, Hollywood, and advertising. Greenberg associated this with a revolutionary rejection of capitalism.

Many modernists did see themselves as part of a revolutionary culture - one that included political revolution. However, many rejected conventional politics as well as artistic conventions, believing that a revolution of consciousness had greater importance than a change in political structures. Many modernists saw themselves as apolitical, only concerned with revolutionizing their own field of endeavour. Others, such as T. S. Eliot, rejected mass popular culture from a conservative position. Indeed one can argue that modernism in literature and art functioned to sustain an elite culture which excluded the majority of the population.

Modernism's reception and controversy

The most controversial aspect of the modern movement was, and remains, its rejection of tradition, both in organization, and in the immediate experience of the work. If there is a fundamental idea of modernism it is that inner existence, for example in experiencing beauty, should be consonant with material necessity, and that art and human activity should, and could, be moulded to do this. This dismissal of tradition also involved the rejection of conventional expectations: hence modernism often stresses freedom of expression, experimentation, radicalism, and primitivism. In many art forms this often meant startling and alienating audiences with bizarre and unpredictable effects. Hence the strange and disturbing combinations of motifs in Surrealism, or the use of extreme dissonance in modernist music. In literature this often involved the rejection of intelligible plots or characterisation in novels, or the creation of poetry that defied clear interpretation.

Because of its emphasis on individual freedom and expression, and its emphasis on the individual, many modern artists ran afoul of totalitarian governments, many of which saw traditionalism in the arts as an important prop to their political power. Two of the most famous examples are the Soviet Communist government rejected modernism on the grounds of alleged elitism; and the Nazi government in Germany deemed it narcissistic and nonsensical, as well as "Jewish" and "Negro" (See Anti-semitism). The Nazis exhibited modernist paintings alongside works by the mentally ill in an exhibition entitled Degenerate art (Louis A. Sass (Bauer 2004) compares madness, specifically schizophrenia, and modernism in a less fascist manner by noting their shared disjunctive narratives, surreal images, and incoherence). Accusations of "formalism" could lead to the end of a career, or worse. For this reason many modernists of the post-war generation felt that they were the most important bulwark against totalitarianism, the "canary in the coal mine", whose repression by a government or other group with supposed authority represented a warning that individual liberties were being threatened.

In fact, modernism flourished mainly in consumer/capitalist societies, despite the fact that its proponents often rejected consumerism itself. However, high modernism began to merge with consumer culture after World War II, especially during the 1960s. In Britain, a youth sub-culture even called itself "moderns", though usually shortened to Mods. In popular music, Bob Dylan combined folk music traditions with modernist verse, adopting literary devices derived from Eliot and others. The Beatles also developed along these lines, even creating atonal and other modernist musical effects in their later albums. Musicians such as Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart proved even more experimental. Modernist devices also started to appear in popular cinema, and later on in music videos. Modernist design also began to enter the mainstream of popular culture, as simplified and stylized forms became popular, often associated with dreams of a space age high-tech future.

This merging of consumer and high versions of modernist culture led to a radical transformation of the meaning of "modernism" itself. Firstly, it implied that a movement based on the rejection of tradition had become a tradition of its own. Secondly, it demonstrated that the distinction between elite modernist and mass consumerist culture had lost its precision. Some writers declared that modernism had become so institutionalized that it was now "post avant-garde", indicating that it had lost its power as a revolutionary movement. Many have interpreted this transformation as the beginning of the phase that became known as Postmodernism. For others, such as, for example, art critic Robert Hughes, postmodernism represents an extension of modernism.

One deep element of modernism has been alienation, either of the individual from self, or from society, or from the "natural" basis of existence. For this reason there have been repeated "anti-modern" or "counter-modern" movements, which seek to emphasize holism, connection and spirituality as being remedies or antidotes to modernism. Such movements see Modernism as reductionist, and therefore subject to the failure to see systemic and emergent effects. Many Modernists came to this viewpoint, for example Paul Hindemith in his late turn towards mysticism. Writers such as Paul Ray and Sherry Ruth, in Culture Creatives, Fredrick Turner in A Culture of Hope and Lester Brown in Plan B, have articulated a critique of the basic idea of modernism itself: that individual creative expression should conform to the realities of technology, and instead that individual creativity should make every day life more emotionally acceptable.

In some fields the effects of modernism have remained stronger and more persistent than in others. Visual art has made the most complete break with its past. Most major capital cities have museums devoted to 'Modern Art' as distinct from post-Renaissance art (circa 1400 to circa 1900). Examples include the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Such galleries (and popular attitudes) make no distinction between modernist and postmodernist phases, seeing both as developments within 'Modern Art'.

Modernism outside the West

Modernism, while a Western movement, has been both influenced by, and influential upon, other societies. One example is the absorption of the styles of Japan towards a taste for horizontality in domestic structures, functionalism, and tectonicity, as well as spareness of vocabulary and the use of line rather than ornament to create style. The translations of Japanese and Chinese literature showed to many Western artists that there was a long, continuous and consistent tradition which was not based on the norms they were used to. Artists such as Vincent van Gogh were inspired directly by models from Japan and China, such as woodblock prints. Ezra Pound's long relationship with Chinese poetry, beginning in 1913, would lead to his translating some of Li Po and publishing haiku in English.

This absorption of Eastern philosophy and style went beyond the surface, and included re-examination of such Western ideas as Christianity from the perspective of Eastern values and concepts. Composers such as Gustav Mahler and Claude Debussy, poets such as Rainer Maria Rilke and architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright would all find aspects of the Eastern traditions of art that would be congenial to their own ideas.

At the same time, trade, mechanisation, and "modernisation" plunged the world outside of the West into a different kind of turmoil. Western powers overran or pressured cultures and states that had existed for centuries or even millennia, and the need for resources created new trade and power structures. Many nations were forced to Westernise and modernise their economies and armed forces. This brought with it a different kind of Modernism which was based on adoption of Western forms and norms on to pre-existing cultures. The result was an explosion which, while clearly related to modernity and modernism, was not specifically Western, nor directed at being a mere extension of Western modernism.

One example of this is the rise of a generation of architects, artists and writers who studied in the West, but returned to their native countries to produce work in the expanding tradition of Modernism. Maekawa Kunio, an architect from Japan, for example, studied in Paris, but returned to Tokyo in the 1930s to become a leading advocate for Modernism in his native land.

Bali's gamelan gong kebyar provides a example of homegrown musical modernism featuring explosive changes in tempo and dynamics that are comparatively modern in relation to traditional Balinese music as European influenced modernism is to traditional European influenced culture.