Oil painting -> Painting Styles -> Realism

Realism

Realism is commonly defined as a concern for fact or reality and rejection of the impractical and visionary. However, the term realism is used, with varying meanings, in several of the liberal arts; particularly painting, literature, and philosophy. It is also used in international relations. Realism is everyday people, doing everyday things in everyday life.

Realism in visual arts and literature

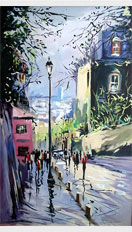

Burial at Ornans by Gustave CourbetIn the visual arts and literature, realism is a mid-19th century movement, which started in France. The realists sought to render everyday characters, situations, dilemmas, and events; all in an "accurate" (or realistic) manner. Realism began as a reaction to romanticism, in which subjects were treated idealistically. Realists tended to discard theatrical drama and classical forms of art to depict commonplace or 'realistic' themes.

Realism in philosophy

Realism in philosophical thinking is the belief that properties, usually called Universals, exist independently of the things that manifest them. Thus a realist would hold that even if one were to destroy all of the manifestations of the color red the universal red would still exist. Competing views contrasted with realism, such as nominalism, hold that universals do not "exist" at all; they are no more than words used strictly to describe specific objects, and do not name separately existing things.

In another sense, realism is contrasted with both idealism and materialism, and considered synonymous with weak dualism. In still a third and very contemporary sense, realism is contrasted with anti-realism.

Both these disputes are often carried out relative to some specific area: one might, for example, be a realist about physical matter but an anti-realist about ethics.

Increasingly these last disputes, too, are rejected as misleading, and some philosophers prefer to call the kind of realism espoused there, "metaphysical realism," and eschew the whole debate in favour of simple "naturalism" or "natural realism", which is not so much a theory as the position that these debates are "ill-conceived" if not "incoherent," and that there is no more to deciding what is really real than simply taking our words at face value.

Realism in international relations

The term "realism" comes from the German compound word "realpolitik", from the words "real" (meaning "realistic", "practical", or "actual") and "politik" (meaning "politics"). It focuses on the balance of power among nation-states. Bismarck coined the term after following Metternich's lead in finding ways to balance the power of European empires. Balancing power meant keeping the peace, and careful realpolitik practioners tried to avoid arms races. However, during the early-20th Century, arms races (and alliances) occurred anyway, culminating in World War I.

Realism makes several key assumptions. It assumes that the international system is anarchic, in the sense that there is no authority above states capable of regulating their interactions; states must arrive at relations with other states on their own, rather than it being dictated to them by some higher controlling entity (that is, no true authoritative world government exists). It also assumes that sovereign states, rather than international institutions, non-governmental organizations, or multinational corporations, are the primary actors in international affairs. According to realism, each state is a rational actor that always acts towards its own self-interest, and the primary goal of each state is to ensure its own security. Realism holds that in pursuit of that security, states will attempt to amass resources, and that relations between states are determined by their relative level of power. That level of power is in turn determined by the state's capabilities, both military and economic. Moreover, Realists believe that States are inherently aggressive (“offensive realism”), and that territorial expansion is only constrained by opposing power(s). The principal Realist theorists are Carr, Morgenthau, and Waltz.

There are two sub-schools of realism: maximal realism and minimal realism. The theory of maximal realism holds that the world order centers on the hegemon, the most powerful entity in the world, and that smaller entities will align themselves with the hegemon out of political self-interests. Under maximal realism, the position where there are simultaneously two equally powerful co-hegemons (such as was the case during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union) is an inherently unstable one and that situation will inevitably collapse into a more stable state where one nation is more powerful and one is less powerful.

The theory of minimal realism holds that non-hegemonic states will ally against the hegemon in order to prevent their own interests from being subsumed by the hegemon's interests. Under the minimal-realism theory it is possible to have two equally powerful co-hegemons with whom a smaller entity may ally in turn depending on which hegemon better fits with the smaller entity's policies at the moment (playing both sides against the middle).

Thus, maximal realism predicts that the most common state of world politics is a hegemonic order, and minimal realism predicts a carefully maintained balance of power. The difference in application can be seen, for instance, in the post-Cold War period. Many minimal realists predicted that, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Europe and Japan would move away from the remaining superpower, the United States. Maximal realists tended to predict that most countries would seek stronger ties with the U.S.

Several critiques were raised against the realist school. One problem is that there are in fact authorities above states capable of regulating inter-state relations. There are organizations like the U.N., WTO, ISO as well as multitudes of multinational organizations and companies. While none of these organization has the powers of a full government, they do have a considerable influence over the actions of states. According to this view, American efforts to receive U.N. support for the invasion of Iraq illustrate the power of the U.N. Had the U.N. no power, as realists would claim, it would have never played any role in the run-up to the war. Further criticism of political realism says that realism has an incorrect concept of a state. States are not actors but rather large organizations. It is impossible, say the critics, to understand international relations without making this distinction. An illustration of this phenomenon can be found in the difficulties involving signing the CAFTA. In particular, the agreement was ratified by United States Senate only after a considerable delay and uncertainty about the outcome.